Introduction to std::chrono

Filed Under: Programming

How many times have you tried to call a function that alleges to return a time value only to realise you don’t know what units the value is in? Or that takes a time value as a parameter, but doesn’t specify whether the value is expected to be in milliseconds, seconds, or hours?

// What is it? I guess milliseconds? Could be microseconds!

int GetGameTime();

// deltaTime is probably in seconds?

void TakeStep(const float deltaTime);

Hopefully there are comments somewhere near the declaration of the function that can help straighten things out, but you may not be so lucky. You may have to read through lines and lines of code to see how these functions are used before you understand what units they use.

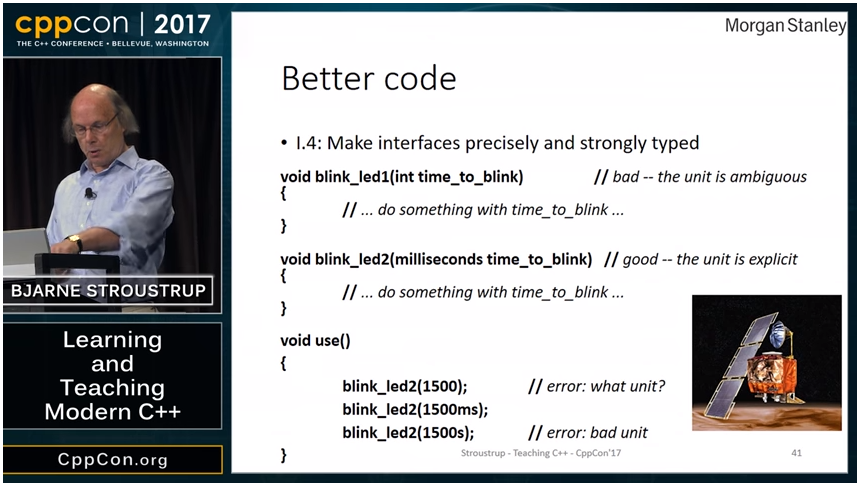

APIs like this are hard to understand at a glance and can cause a lot of bother. Consider the potential cost of a bug that occurs when an API expects milliseconds, but is passed seconds. Here’s a slide from Bjarne Stroustrup’s CppCon 2017 keynote:

…in which he pointed out that the failure of the Mars Climate Orbiter was due to a software bug that would have been completely avoidable had a particular API encoded the units of measurement it used (in this case, imperial instead of metric).

UPDATE: STL pointed out in a Reddit comment that Stroustrup’s slide is wrong! But the sentiment is correct, anyway.

And so we have strongly-typed time values like C#’s System.TimeSpan provides. In the world of C++, many libraries and frameworks have their own time type. For example, SFML has sf::Time and sf::Clock. sf::Clock::getElapsedTime returns a sf::Time, which can be compared to, added to and subtracted from other instances of sf::Time. Then it can provide its value as seconds (float), milliseconds (int32) or microseconds (int64).

Until C++11, the language didn’t have a standard way to represent times. Then chrono was added to the standard library.

chrono exists at a higher level of abstraction than sf::Time/sf::Clock. The library consists of three concepts: clocks, time points and durations.

Clocks

Clocks are time providers, consisting of a starting point (“epoch”) and a tick rate. A clock has a now() member function that returns how much time has passed since the starting point. The standard library provides three clocks for your basic out-the-box time-getting functionality, the main one being system_clock. If you need to, you can create your own class or bundle that satisfies the Clock concept.

Time Points

time_point represents how much time has passed since the start of the clock it is defined in terms of. For example, a time_point<system_clock> would record how long since the system_clock started. You’d initialise it like so:

time_point<system_clock> t = system_clock::now();

You won’t be able to initialise it with the now() of a different clock because its time_point type isn’t convertible to that of the original clock.

time_point<system_clock> u = steady_clock::now(); // Error!

(Note: because high_resolution_clock may be an alias to system_clock, it may be possible to convert between their time_point types. Don’t count on it, because your code may not be portable if you do.)

At runtime a time_point is a simple arithmetic type like an int or a float, and it can be added to and subtracted from other time_point instances, as long as they all come from the same clock.

Durations

A duration is, like a time_point, just a puffed-up arithmetic type. Unlike time_point, it’s not coupled to a specific clock type at compile time.

Along with its runtime value the duration contains a compile-time ratio specifying the units of time that value represents. A ratio of 1:1000 means milliseconds, a ratio of 1:1,000,000 means microseconds. The default ratio is 1:1 – that is, the default units for durations is seconds. The standard library defines some ratios for us in the <ratio> header.

You declare and set durations like so:

(duration::count returns the value of the underlying arithmetic type.)

// integral representation of 10 milliseconds

std::chrono::duration<int, std::milli> d(10);

// d.count() == 10

d = std::chrono::milliseconds(5);

// d.count() == 5

d = std::chrono::seconds(10);

// d.count() == 10,000

Casting from seconds to milliseconds can happen implicitly, but in other cases it is necessary to use duration_cast.

User-defined Literals

These are wonderful little things of which chrono provides a handful. The s literal, for example, turns its operand into a duration<unsigned long long> or duration<long double>.

using namespace std::chrono_literals;

// integral rep of 1 second

std::chrono::duration<int> t1 = 1s;

// floating-point rep of 1 second

std::chrono::duration<float> t2 = 1s;

// floating-point rep of a fraction of a second

std::chrono::duration<float> t2 = 1ms;

Conclusion

Finally, here is the API from the beginning of this article, rewritten to use chrono:

#include <chrono>

std::chrono::duration<int, std::milli> GetGameTime();

void TakeStep(const std::chrono::duration<float> deltaTime);

And we can all sleep a little better at night.

UPDATE: Reddit user kalmoc mentioned Howard Hinnant’s date time library. I haven’t used it yet but it looks like a useful extension of chrono.